Scientists have unearthed Asia’s first fossil record of mulberry from the Gurha lignite mines near Bikaner in western Rajasthan, a finding that they say, indicates the existence of a warm, humid climate in north-western India 56 million years ago.

Although mulberry (Morus genus) is now widely grown in India and Asia, no fossils of the tree have yet been found in the continent, say a team of scientists from HBN Garhwal University in Uttarakhand, University of Calcutta, and Sidho Kanho Birsa University in Purulia in West Bengal. They report in the journal Review of Paleobotany and Palynology that the presence of the fossil suggests that mulberry was an important component of tropical–subtropical evergreen forests growing in a warm humid climate in the area during the Eocene period, that is, 56-39 million years ago.

According to them, mulberry subsequently declined from the area which is now dry with desert vegetation, probably because of the drastic climate and latitudinal change in the area, related to the formation of the Himalayas, and rainfall seasonality since the Eocene.

Most mulberry trees are now found in the ‘Old World tropics’, particularly in Asia and Indo-Pacific Islands.

Mahasin Ali Khan, assistant professor at the department of botany, Sidho-Kanho-Birsha University, and one of the paper authors, told Mongabay India that “to date, no fossil Morus has been reported from Asia.”

This lack of fossil evidence limits scientists’ understanding of the diversification and evolution of Morus in Asia, Khan says. Leaf and fruit remains of Morus have been reported only from the preceding Palaeocene epoch dating to 66 million to 56 million years ago; and the later 33-million to 23-million-years-old Oligocene sediments of the United States. Hence, the Indian team’s discovery of Morus leaf remains from the early Eocene of India “is remarkable” and constitutes the first recognition of this mulberry genus from the Cenozoic (66 million years ago to present) sediments of Asia,” their report says.

Earlier fossil studies also indicate a tropical to sub-tropical, warm humid climate in western Rajasthan, unlike present-day dry, desert conditions, the report says.

The equatorial position of the Indian sub-continent during the Eocene period was “ideal” for the growth of tropical evergreen forests, while recovered fossils dating to the Eocene period from lignite mines in western Rajasthan also indicate the presence of tropical rainforests in western India, the report says.

n India, the genus is no longer found in western Rajasthan where the fossil was discovered, and the authors attribute its extinction from the area possibly to “drastic climate change” as well as latitudinal movement in the area as a result of the collision of the Indian and Eurasian plates, uplift of the Himalayas and Tibetan plateau, and evolution, strengthening and long-time fluctuations in the monsoonal conditions.

The scientists hope that the new study “provides a launching pad” for further detailed studies of the newly collected materials, providing a clear picture of their implications.

Eocene plant fossils

Scientists are particularly interested in the Eocene period, characterised by warm temperatures, for studies on the evolution, diversity, and dispersal within and among continents of modern-day plant and vertebrate species. While the authors report that the finding of the fossil in the region “provides unambiguous evidence” that mulberry plants were well-suited to the climatic conditions in the Eocene period, not all paleobotanists agree.

Rakesh Mehrotra, president of the Palaeobotanical Society and a scientist with the Birbal Sahni Institute of Paleosciences, Lucknow, says that he does not agree with the conclusions of the study as mulberry “is a temperate genus found naturally in central China and is cultivated in many countries, including India.”

“Its presence during the early Eocene in India is doubtful as the fossil flora during the period was typically tropical in nature,” says Mehrotra. Fossils recorded during the early Eocene of western India, including Gurha mine, support his theory, Mehrotra adds.

He points out that the early Eocene is characterised by a warmer phase, even at high latitudes. The carbon dioxide level was also higher, ranging from 1000 to 2000 parts per million (ppm) due to the increase in volcanic activity.

In 2018, Mehrotra and colleagues had published in Review of Paleobotany and Palynology that “the climate dynamics of the Indian subcontinent and biotic exchange between the neighbouring continents can be traced by studying the Eocene fossil assemblages which are nicely preserved in the rock records.” Fossil records from early Eocene sites are important for their potential contribution to our understanding of interactions between climate and biota, it said.

In the western part of the Indian subcontinent, extensive lignite deposits are known in Gujarat (Kutch and Cambay basins) and Rajasthan (Barmer and Bikaner-Nagaur basins). Based on analysis of nearest living relatives (NLRS) of the plant and animal remains in the lignite deposits of these areas, ‘it has been concluded that a highly diversified tropical evergreen forest was present in most of the basins of western India,” says Mehrotra.

The equatorial position of the Indian subcontinent during the early Eocene also supports this theory, says Mehrotra.

The lignite mines of Gujarat and Rajasthan have proved to be a rich treasure house of Eocene fossils, pointing towards the existence of dense tropical forests in the arid region of today and equatorial climatic conditions in the Indian subcontinent 55 million years ago.

In 2019, Mehrotra’s team reported a rare fossil record of a fruit of Mallotus mollissimus, a plant from the spurge family and whose fruits are too soft to be preserved, from the Gurha mines of Rajasthan. The fossil indicates the existence of tropical forests in the area and the origin of the plant from Gondwanaland.

Similarly, a fossil wood found in the Vastan lignite mine of the early Eocene age near Surat district in Gujarat, by Mehrotra’s team, shows a strong resemblance to the modern genus Chisocheton of the mahogany family of trees known as Meliaceae. Such plant fossils are the best source to reconstruct the past environment of any region, and the locality likely had a “luxurious, highly diverse tropical evergreen forest” in contrast to the tropical thorn forest of the present-day Mehrotra and colleagues’ 2018 report in Paleoworld says.

“This early Eocene highly diverse equatorial forest, once covered a significant portion of the Indian subcontinent, is now restricted in fringes known as the Western Ghats in south India attesting to changes in climate,” it adds.

Read the full report here: https://india.mongabay.com/2021/12/asias-first-mulberry-fossil-unearthed-in-rajasthans-lignite-mines/

#science #paleontology #fossils

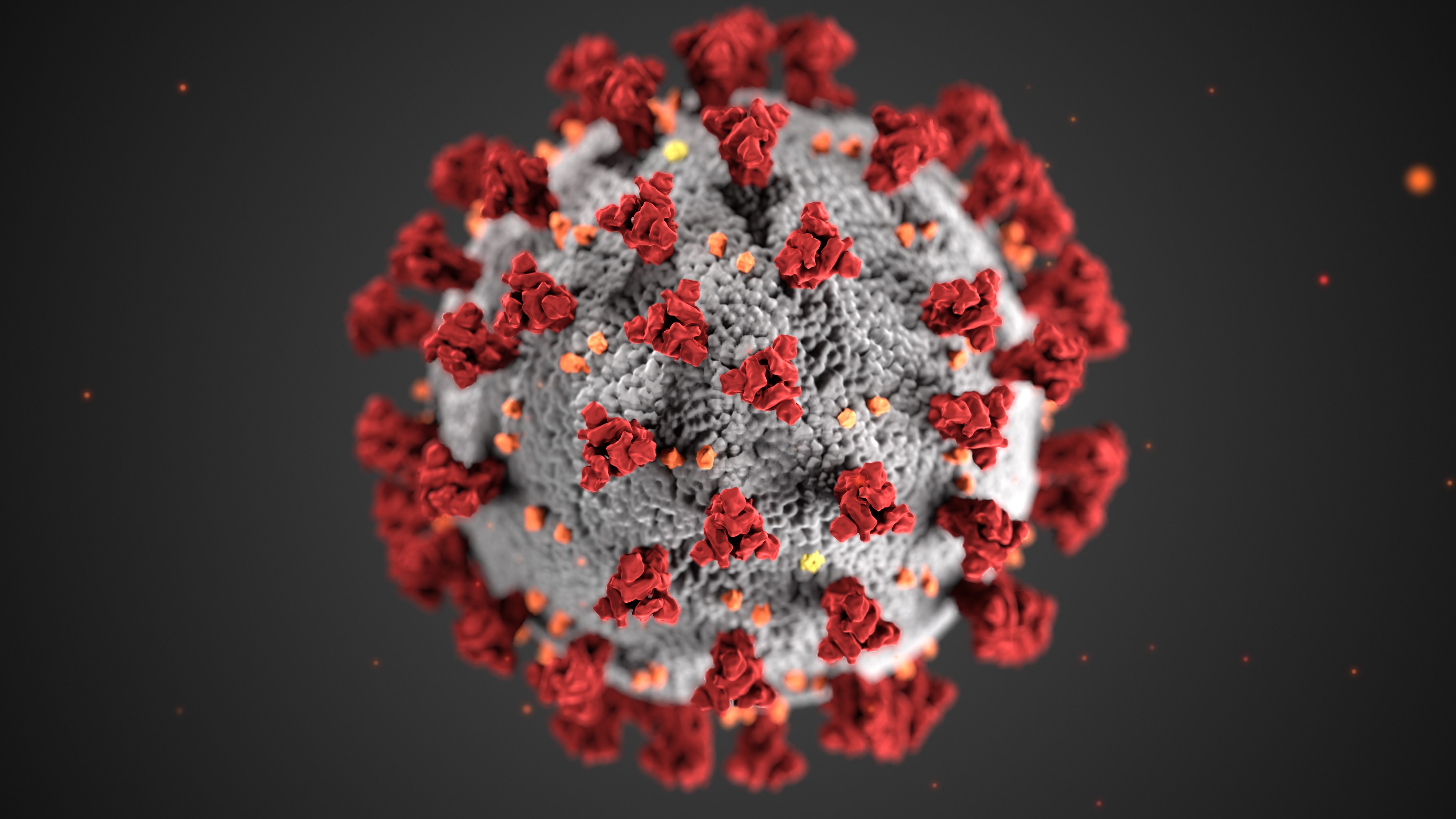

As India enters an extended lockdown to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, experts are worried whether community spread of the virus has started, and if so to what extent; or whether the country still has a small window of opportunity to stop the spread.

As India enters an extended lockdown to slow the spread of the novel coronavirus, experts are worried whether community spread of the virus has started, and if so to what extent; or whether the country still has a small window of opportunity to stop the spread.